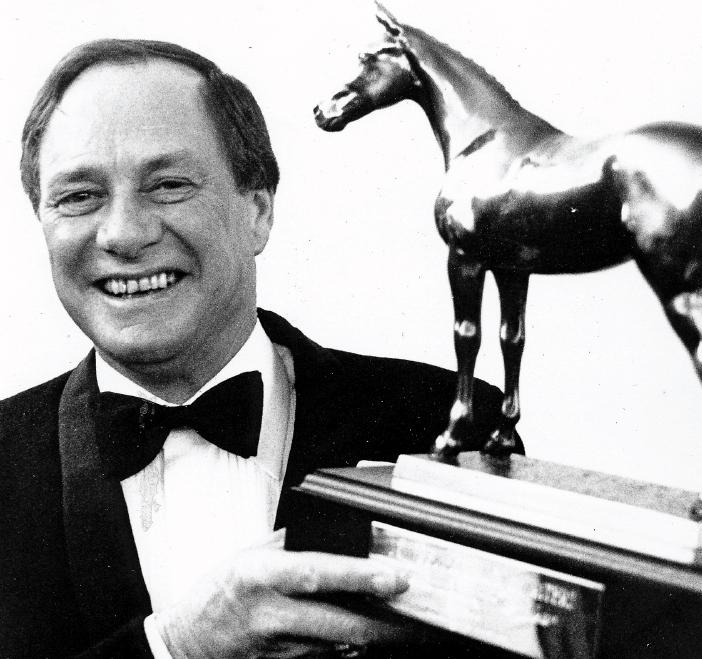

The great trainer passed away peacefully this morning at 12.15 AM 23 December 2022, aged 91

Kim Clotworthy described him as a ‘genius,’

Peter Grieve said he was ‘outstanding in every way – he worked and played hard, but the horses always came first.’

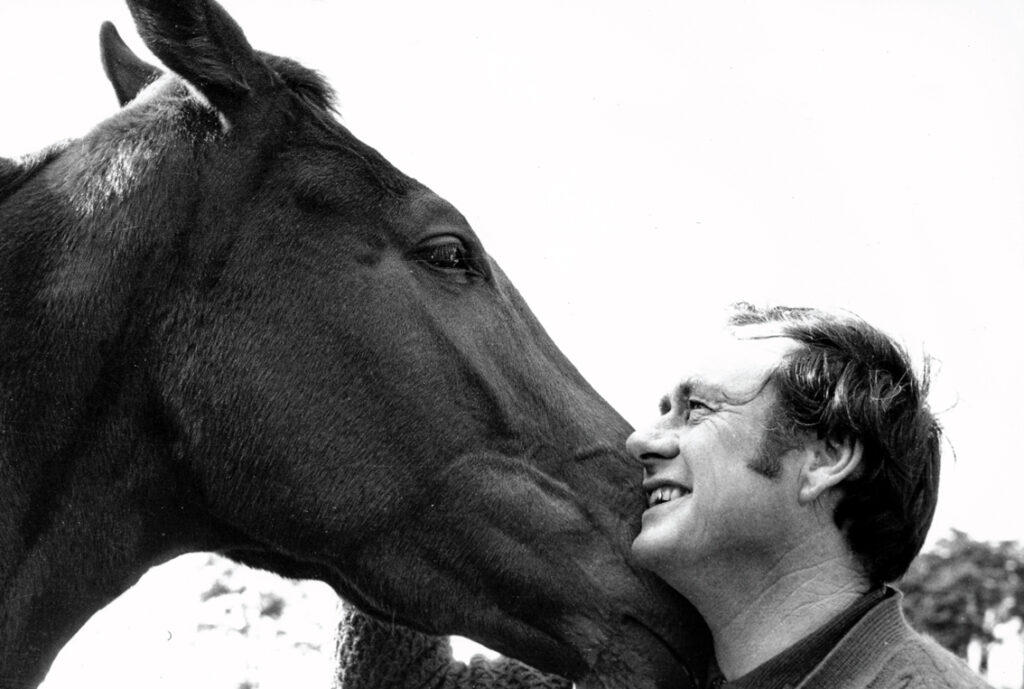

Keith Haub: ‘He was half horse and half man – he understood horses and horses understood him.’

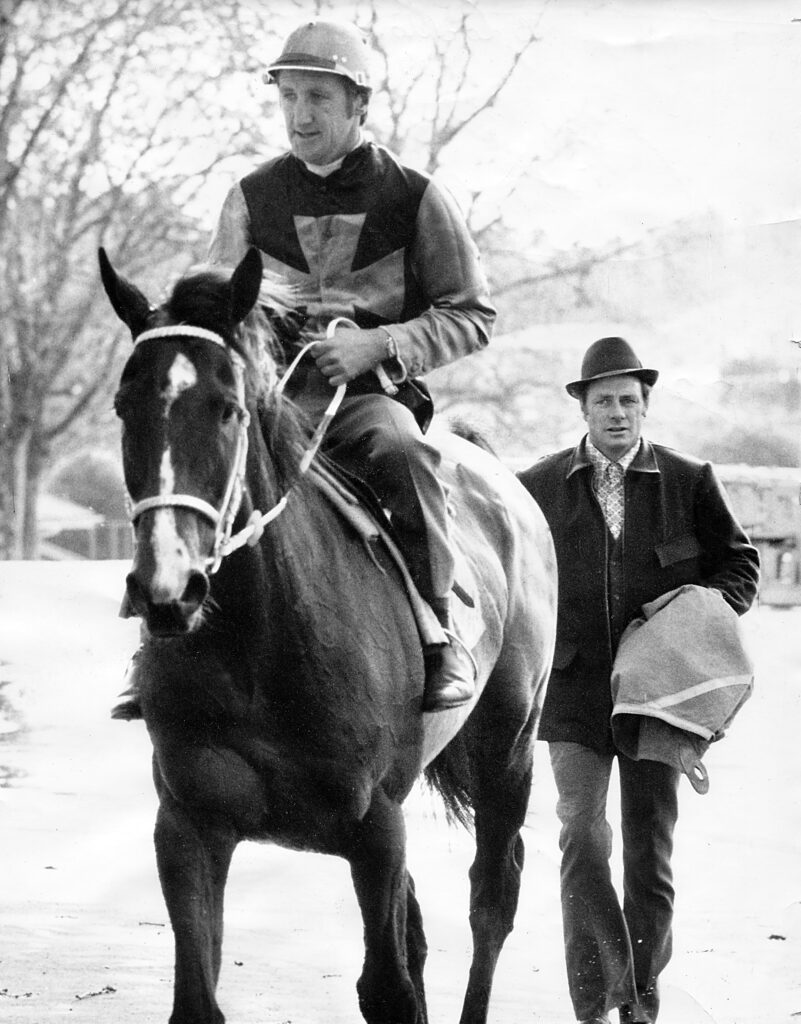

Remembering the life of Colin Jillings, by Brian de Lore

Published 23 December 2022, updated from a BdL article in The Informant July 2018

Colin Jillings survived ‘the school of hard knocks’ to reach the top

Life was tough for kids growing up during World War II. Along with food rationing, it was a time of economic hardship with a scarcity of commodities and a lifestyle that required plenty of discipline, providing few luxuries.

Such was the early life of Colin Maurice Jillings, born amid the great depression on 11 March 1931 and grew up through the tough war times, which undoubtedly had a bearing on the person he became and the success he would later achieve.

When the war ended in 1945, Jillings was just 14 years old but had already been an apprentice jockey for over two years, having received his indentures for the start of the 1943-44 racing season.

“I was only 12 but put my age up to 13 to start my apprenticeship,” recalled Jillings; “they didn’t ask for birth certificates. It was different in those days – it was the war years.”

Jillings rode in 20 apprentice-only races before getting granted his full apprentice licence, allowing him to ride in open races. But that amounted to the least of this ambitious 12-year-old’s worries; his lowest weight recorded on his first licence read as six stone (38.1kg).

As a 10-year-old, the young Jillings would wander into Ivan Tucker’s stable yard at Ellerslie and be told to ‘scram’ by the leading trainer. On one occasion, after getting chased out the gate, Tucker came around the corner only minutes later to see the young rascal coming back through the gate atop a gelding named Brazilian returning from his afternoon walk.

“Brazilian was a jumper owned by Dr and Mrs Roberts from Huntly,” recalled Jillings in July of 2018. He remembered the circumstances vividly. “No, I didn’t give up going to the stable. I was only nine or ten and then later became the leading apprentice when I was still going to school.”

Jillings wouldn’t go away, and eventually, Ivan Tucker resigned himself to legging him up on the quiet horses, and the association began. Horses acted like a magnet to the young Jillings – hardly surprising with the racing blood flowing through his veins.

His father, Ledger Jillings, had a great love of horses and had spent much of his youth at a trotting stable while his grandfather Henry was a jockey, and his uncle had ridden many winners in the lightweight jockey ranks.

Before wandering through the gate at Tucker’s yard, the Jilling-kid had given the sofa at home many a whip hiding. Racing consumed young ‘Jillo’ and no doubt existed in his mind on the career path he would head down.

In those early days, no difference between discipline and bullying existed, and Jillings recalled: “Ivan Tucker was very tough – he used to get his middle finger and punch you in the muscle on the arm.”

Tucker soon recognised that horses that usually pulled hard would relax and travel for Jillings. He had a way with thoroughbreds and always showed Tucker the required potential.

But little more than six months into his apprenticeship and just a couple of weeks before his 13th birthday, the young jockey with only a handful of rides behind him he had a horrific fall.

“Riding trackwork one foggy morning at Ellerslie on the number three grass, I fractured my skull when the horse I was riding collided with a horse ridden by Grenville Hughes – Grenville picked me up and helped me get to the hospital. I was out of action for 12 months and put on weight, too.”

Most young jockeys would not have returned, but the young Jillings didn’t lack courage and happily returned to riding a year later. “I was an apprentice jockey for a long time,” explained Jillings, “because I was still going to school.

“I used to catch the eight minutes to nine bus to go from Amy Street to attend St Peters School run by the Christian brothers, and there were a couple of mornings a Brother Lynch gave me six of the best for being late to school.”

“My mother had to write a letter to him to tell him that I had special permission to catch that bus from Ellerslie to Khyber Pass even though it didn’t get me there quite on time. I only suffered that on two mornings, and the problem was then solved.”

Jillings rode trackwork in the morning before going to school and then returned to work at the stable in the afternoon. Despite the distraction, he finished top of the class at St Peter’s in his final year, aged 15.

The young Jillings rode 13 thirds before he rode his first winner, but in his second full season as an apprentice, he notched up 28 wins, placing him second on the apprentice list in the 1945-46 season behind one of the all-time great apprentices of the time, Keith Nuttall.

“I was leading apprentice in 1946-47 but wasting hard,” Jillings proudly recalled. “By then I was walking 7st. 10lb and would ride 7st., and would start wasting Wednesday, have half a cup of tea at lunchtime, a piece of toast, and half a cup of tea at night time and do the sweatbox on Thursday and Friday nights. We had one at the stable. I used to lose the weight, but it took a lot out of you.”

He recalled the inevitable retirement for Colin Jillings-the jockey: “My last ride was on Super Vaals in 1947 at Ellerslie, and by then I was walking ten stone three pounds (65.4kg) and riding nine stone (57.1), so I was wasting 17 pounds by then – I was always pretty tall. I grew quite a lot in that 12 months I was out.”

Jillings had ridden 64 winners by this stage, was 16 years old, and would have liked nothing more than to have fulfilled his potential as a jockey. He had given his all and had grown too big, but his ability in the saddle didn’t go unnoticed.

Legendary horseman of both codes and gifted writer Clyde Conway wrote this accolade for Jillings in 1957: “One day at Te Aroha in 1946, Colin was riding Kill Fast. He literally pushed his mount up on the line to split a dead-heat with Gay Fault.

“This prompted Charlie Gomer to remark to Skipper Ryan and myself (we were acting as stewards under him), That boy Jillings can ride. Even Hector Gray could not have got more out of that horse than Jillings did. If he could stay light, he could be as good a rider as this country has ever seen.”

Conway continued, “This was high praise indeed, for those that knew him were well aware that Charlie Gomer was never lavish with such comments. Furthermore, his years of reading races had made him a shrewd and hard-headed critic of jockeys and race riding.”

But as Conway himself conceded, “all the ability in the world is no good when you are walking over the nine stone mark and standing five foot 10 and a half inches in your socks.”

After discovering this long-lost quote buried in one of Jillings’ scrapbooks that his mother had carefully kept, Colin remembered Gomer: “Charlie Gomer was a chief stipe, and he was a very tough man – as tough as they come and well known for it.”

Phase one of the Colin Jillings racing career had ended, for try hard as he could to keep his weight down, and failing, a new career now beckoned. The opportunities as a hurdle jockey soon dried up.

The battle against increasing weight for any talented, young jockey with premiership aspirations is invariably about genetics more than a propensity to indulge in pizza. This was certainly the case for 16-year-old Colin Jillings when he rode his last race – a winning one which was the 64th success of his abbreviated riding career.

“My last ride was on Super Vaals in 1947 at Ellerslie, and by then I was walking ten stone three pounds (65kg) and riding nine stone (57kg), so I was wasting 17 pounds by then – I was always pretty tall,” said Jillings

“I became the private trainer for Albert Brownson when I was 19, explained Jillings. Before that, and between retiring from riding and starting training, I worked in the freezing chambers for two or three years.

“I took two horses to Australia and they both won – we sailed on the Monawai on the 1 February 1950 with Lady Finis and Gayriol, and we only took Lady Finis as a mate, but she did that well, and although she was only small, she was very good -she won three and ran 5th in the Doncaster.”

From jockey to trainer: Colin Jillings made the transition with immediate success

With these two horses and the trip away, his training ability began to manifest. As a 19-year-old, from just nine race starters, he collected four wins and two placings – Jillings, the trainer, had hit the ground running.

“In those days you had to be 21 to do anything, so Brownson had to be my guarantor for all the costs that I incurred; I was a private trainer, but all I did, really, was get a wage.

“Lady Finis was only small, but by God she was good. She won three and Gayriol won one but I had Gayriol going for £12,000 at Randwick on an all-up, and she was beaten a nose – a nose after a bad ride – well, I didn’t exactly cry, but there may have been a few tears rolling down my face.

“Lucky I didn’t win – probably would have killed myself with that much money. I came home thinking I was TJ Smith and Bart Cummings all rolled into one, and then Brownson sacked me, and it was probably fair enough, too.”

If Jillings had been feeling a little overly pleased with himself at that point of his career, he soon came back down to earth. Following that speed bump, he found himself out of racing again and down in Kinleith with his uncle to resume his career as a cable jointer.

“At the pulp and paper mill, we did all the cable jointing for them. I was there for about three years living in a two-man hut with my uncle, and we worked six days a week with only Sundays off. It was in Tokoroa that I met Alison.”

But the lure of the turf beckoned again. He purchased a gelding named Armed trained at Takanini by Morrie Bowden. Eventually, Jillings took over the training himself, prepared Armed from a farm in Tokoroa, and won a couple of races at Matamata, on one occasion ridden by highweight jockey Jim Gibbs, whose only two rides for Jillings both won.

Armed suffered from unsoundness, but Jillings nevertheless saddled him up to win a Grand National Hurdle – testimony to the trainer’s horsemanship even at such a tender age. Meanwhile, he won a couple of races with Swift View, and the urge to go training full-time proved too great to resist.

Jillings left Kinleith and returned to Takanini, starting out with Armed, Goldbearing, and Durain, quickly made an impression and steadily built up a team of horses and a new clientele.

“I went back to Takanini to train in 1953,” he recalled. “My old boss Ivan Tucker then got disqualified for 12 months about 1954, and he appealed and got an extra 12 months, and that’s when I took over his stable. I moved in, paid him rent and I got Bright Gem, Emphatic and Bertha Fox, and I picked up Yemen as a two-year-old, too.”

In 1956 Jillings won the Auckland Cup with Yemen and married his Tokoroa sweetheart, Alison, a marriage of 65 years until Alison’s passing in 2021 at the couple’s townhouse at the Sir Edmund Hillary Retirement Village in Remuera.

On marriage, Jillings would joke: When you marry, you get an asset or a liability; well, I got an asset,” and then after a pause and a grin, he retorted, “marriage is like a three-ringed circus; first you get the engagement ring, then you get the wedding ring, and then you get the suffering.”

Jillo – well-known for his quick wit and memorable quotes

‘Jillo’ as he affectionately became known, all his life had his trademark legendary quick wit and humour, for which he became as famous as for turning out top horses. Always a deep thinker, he had a quote for every occasion, such as, “fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” or “we’ll keep going ahead even if it’s ass-over-head.”

One-time fellow Takanini trainer Frank Ritchie had many days of laughing at the Jillings rhetoric at trackwork and remembers him on one occasion saying: “ya know ol’ son what life’s biggest problem of all is? – the green monster.” He said, “jealousy – never, ever let it get you.

“The other thing he used to say was,” continued Ritchie, “‘never, ever let them know you’re hurting.’ He was talking about a losing bet or losing a horse to another trainer, and he said, ‘even if it’s killing you, never, ever let them know it’s hurting.’”

But while Jillings may have been the ‘poet laureate’ in a different age, he churned out the winners that placed him on a special level in the world of racing. Numerous runs of cheering home Jillings-trained winners far outweighed the occasional bout of ‘hurting’.

If a better trainer than Colin Jillings has lived in the history of New Zealand racing, then it’s an academic argument only – a bit like comparing Frankel with Phar Lap.

Jillings himself modestly put his success down to good fortune but did concede this: “I had a lot of luck as a trainer, but I worked hard at it, and it’s like everything in life – ‘as you sow – so shall you reap.’ I had a good horse every year but never had a big team in work. Today, it’s a numbers game, but I had a personal, hands-on approach.

“Care and attention were the most important factors for me,” came the Jillings answer he shot back to the question of ‘getting the best from your horse.’ None of this ‘she’ll be right’ – it’s got to be right.”

That manner of precision and work ethic saw Jillings train 1,372 career winners, including 703 in partnership with Richard Yuille, from a career that stretched 54 years from 1950 to 2004. Great thoroughbred names such as Stipulate, Yemen, McGinty, Uncle Remus, The Phantom Chance, Brockton, Perhaps, Lawful, Honourbright, Tiger Jones, Old Son, Port Royal, El Tombo, Sharivari, Beauzami, Springtide, Silver Image, Gold Ducal, Marquess, Athenaia, Shamrock Queen and Biltong only to name a few.

Long-time friend and owner Peter Grieve said of Jillings, “I went away with him a lot, and the horses always came first. He had two-year-olds, jumpers, stayers, fillies, Cup horses – everything; he could train them all equally as well.”

“Stipulate was the best horse I ever had – when I think what he went through,” said Jillings when pressed for a favourite. “He was a great horse; really tough – was he good! He won the Auckland and New Zealand Cups, should have won the Wellington Cup – he got beaten narrowly by Great Sensation, and it was my fault.

“I’d eased up on him a bit before the race, but he came out on the last day and beat the best weight-for-age field you’ve ever seen. And he bolted in. He was a stallion but was quiet – he wasn’t one of those that would roar or anything like that – a thorough gentleman, a great horse to train – tough – you could hit him with an axe, and it would bounce off him.”

Auckland Cup winner Perhaps also became a Jillings favourite. He said: “She was beautiful, Perhaps, you could have brought into this lounge – she had such a kind temperament. Sandy (Warren Sandman) who owned her was just the greatest man and owner you could have ever wished to train for.”

He did not suffer fools

Jillings didn’t suffer fools very easily and was notoriously tough on jockeys, but regular rider Bob Vance and the trainer had a long and successful association that survived the odd difference of opinion and developed into a bond of massive mutual respect.

“He just had a great eye for the small detail, said Vance. “You could walk a horse to the track, and if there was a problem, he would spot it from 50 metres away – he would tell you to go back and fix it. For the small detail, he was superb.

“He never had a big team, but his planning was unbelievable. When we went to the Cox Plate with The Phantom Chance, he knew what he was doing every day before he went.

“And he invariably always had the horse 100 percent on race day. He would target a big race and knew he would get the best out of his horse on that day. Everything had to be perfect for him down to the smallest detail – stuff most trainers wouldn’t think about.”

On Vance, Jillings said, “I put him on everything, but when I gave him instructions, he could carry them out to a tee. One day he drew 18 at the barrier in a two-year-old race, and he told all the other jocks behind the barrier, ‘watch out you fellas, I’m going straight to the fence,’ and he said there was only one jockey he was frightened of in that race and that was Chris McNab.

“But he got to the fence, and he won the race. He rode Uncle Remus as an apprentice, I might be a bit biased, but by god, he was a good rider – a really top rider.”

Of all the characters associated with Jillings over his long career, none has been more colourful than racecaller and McGinty part-owner, Keith Haub. In Australia in one of McGinty’s pre-race press scrums, Jillings was asked by the local scribes if all was well with McGinty going into the race. Jillings replied, “the horse is well, but it’s the owners that are the problem – one is a millionaire, and the other one thinks he’s a millionaire.”

It was yet another example of the Jillings quick wit and command of language although there was more than just an element of truth in that jibe. Haub and Jillings remained firm friends, and the pair always got together with Peter Grieve for regular catch-ups.

“He’s so clever, Hauby,” said Jillings. “There was no better auctioneer; he could sell property; there was never a better racecaller; he could sing and play the guitar as good as anyone – and he could have done anything in life he wanted to.”

On the other hand, Haub rated Jillings a steadying influence on his life: “Very strong on principles,” said Haub. “He had a huge effect on my career – he kept tabs on me. He’s highly principled, and he always listened carefully to everyone – he was a great student of life and took everything in.”

Some people just might construe that if Jillings was keeping tabs on Haub’s life then he must have suffered numerous distractions – but that’s another story.

And just as Frank Ritchie had earlier related, Haub’s take of Jillings as a deep thinker also brought him to tell Haub, ‘the disease that people have and they don’t know what it is – jealously. They don’t know they’ve got it.’

“Watching races from the stand, he hardly ever used binoculars, and he could analyse a race with the naked eye as good as I did with binoculars and still know everything that happened in it.”

In later years, Jillo’s eyesight failed him with macular degeneration setting in, but his memory and wit always remained sharp, and this legendary Hall of Famer, former Racing Personality of the Year and recipient of the Award for Outstanding Contribution to Racing, will never be forgotten as long as racing exists.

And the good times he had with his very good and close mates will remember fondly how he would often address them affectionately as ‘old son.’

A celebration of the life of Colin Maurice Jillings will take place in the Newmarket Room of the Ellerslie grandstand on 5 January 2023 at 2.00 PM.

by Brian de Lore

A greater man I have yet to meet RIP Old Son you will never be forgotten

Wonderful tribute to a great trainer, Brian.

was an apprentice jockey to him in 11986 to 1987 remember the top horse he train was diamond lover greenback she fun and jumpers deductible so regal a few more couldn’t remember my late former bos a top man learn a lots from him

#ripbos

#frommalaysia

I first stepped onto a racecourse in 1960 and the game has been my passion ever since. In all that time, I can’t bring to mind a single person, either licensed or administrator, held in higher regard by his peers. Colin Jillings was a great of our sport at a time when the sport was at its greatest.

I didn’t know him Brian but you brought him to life in this tribute, amazing!

One can only stand and salute the passing of a true champion.

A lifetime in racing brought me into contact with the great man of racing across the globe.

None had my admiration as much as Colin Jillings .

We only knew each other to a certain level but he was the greatest

He may well have been the greatest percentage trainer of all time .

My admiration of Colin Jillings never wavered .

A true character who was able to mix at any level , supported by a devoted wife and family .

Good on you old son

Lex and Sharron ( Snow White) Nichols

Top class tribute Brian.

Jillo was indeed a legend, and a wise and capable one at that.